Category Mughal Empire

طاقتور مغل بادشاہ اکبر

شہنشاہ بابر نے براعظم پاکستان وبھارت کو بزور شمشیر فتح کر کے سلطنت مغلیہ کی بنیاد ڈالی۔ لیکن حقیقی معنوں میں خاندان مغلیہ کو طاقت شہنشاہِ اکبر کے ہی دور میں ملی۔ جلال الدین محمد اکبر کا باپ ہمایوں جب افغانیوں کی یورش سے گھبرا کر ایران جا رہا تھا تو 1542ء میں عمر کوٹ (سندھ) میں اکبر پیدا ہوا۔ پندرہ سال کی جلا وطنی کے بعد ہمایوں دوبارہ تخت دہلی پر قابض ہوا مگر زندگی نے وفا نہ کی اور جلد ہی سیڑھیو ں سے گر کر مر گیا۔ اکبر تیرہ برس کی عمر میں باپ کا جانشین ہوا۔

اسے افغانیوں اور ہیموں سمیت کئی بغاوتوں کا سامنا کرنا پڑ رہا تھا۔ 14 سال کی مسلسل کوشش کے بعد اکبر مالوہ، چتوڑ، رنتھنبور، کالنجر، گجرات اور بنگال کو فتح کرنے میں کامیاب ہوا اور 1576ء تک سارا شمالی ہند اُس کے زیر نگین ہو گیا۔ 1586ء اور 1595ء کشمیر، سندھ، بلوچستان، قندھار اور اُڑلسیہ بھی مغل سلطنت میں شامل ہو گئے۔ شمال کے بعد جنوب میں دکن ، خاندیش، برار اور احمد نگر پر قابض ہو گیا۔ اُس کی سلطنت ہندوکش سے گوداوری اور بنگال سے گجرات تک پھیلی ہوئی تھی۔ اکبر نے اپنی مرکزی اور صوبائی حکومتوں کا انتظام نہایت باقاعدہ کیا۔ ہندوؤں، خاص کر راجپوتوں، سے اُس کا سلوک نہایت اچھا تھا۔ سلطنت کے بڑے بڑے عہدے ہندوؤں کو دیے گئے۔

ابتداء میں تو راسخ العقیدہ مسلمان تھا، لیکن بعد میں کچھ اپنی ناخواندگی کی وجہ سے اور کچھ سیاسی مصلحتوں کے پیش نظر ’’دین الٰہی‘‘ کے نام سے ایک نئے مذہب کی بنیاد رکھی، لیکن چند امیروں وزیروں کے سوا اس دین کو کسی نے قبول نہ کیا۔ اگرچہ اکبر ان پڑھ تھا، لیکن اس کو علوم و فنون کی امداد اور سرپرستی کا خاص شوق تھا۔ بڑے بڑے شعرا، مصور، موسیقار، معمار اور دوسرے با کمال اس کی بخشش اور قدر دانی سے مالا مال ہوتے رہتے تھے اور اس کا دربار دُور و نزدیک کے ماہرین فن کا مرکز بن گیا تھا۔ وہ شہزادوں کی تعلیم و تربیت پر خاص توجہ کرتا تھا۔ اکبر عظیم فتوحات ، معیار اور علم و فن کی سرپرستی کے لحاظ سے دنیا کے بڑے بڑے بادشاہوں میں سے تھا۔ وہ 1605ء میں تریسٹھ سال کی عمر پا کر فوت ہوا۔

محمد واجد علی

ہندوستان کا حکمران ظہیر الدین بابر کون تھا ؟

حال ہی میں ایک مغربی جریدے نے ظہیر الدین بابر کی شخصیت، طرز حکمرانی اور اس کی جوانمری و بہادری پر ایک تفصیلی مقالہ تحریر کیا ہے۔ کیلی شیفسن نے اپنے مقالے میں تحریر کیا ہے کہ برصغیر کا یہ نامور حکمران ماضی میں موجودہ ” ازبکستان “ کا شہنشاہ بھی رہ چکا ہے۔ اپنے چچاؤں کی بے رخی کی وجہ سے اسے 3 سال جلا وطنی میں بسر کرنا پڑے۔ وہ اپنی طاقت مجتمع کرتا رہا، مگر تخت واپس نہ لے سکا۔ افغانستان میں جلا وطنی کے دوران اسے ہندو کش کے پہاڑوں میں بہت کشش نظر آئی۔ لودھی خاندان کا ایک گورنر بھی س کے ساتھ مل گیا۔ اسی قسم کے خاندانی جوڑ توڑ کی مدد سے وہ دہلی پر قائم ”لودھی سلطنت “ کے خاتمے کے بعد انڈیا کا حکمران بن بیٹھا۔ اس کی کوششوں کے بعد مسلمان 3 سو سال تک بلا شرکت غیرے انڈیا پر حکومت کرتے رہے۔

بابر کا تعلق تیموری خاندان سے تھا جبکہ اس کی ماں چنگیز خان کے خاندان سے تعلق رکھتی تھی۔ سینٹرل ایشیاء سے تعلق رکھنے والے اس خاندان کے بارے میں 1868ء تک لوگ زیادہ نہیں جانتے تھے۔ یہ کون لوگ تھے، کہاں سے آئے اور کس طرح اپنی حکومت قائم کرنے میں کامیاب ہوئے؟ ان سوالوں پر زیادہ تحقیق نہیں ہوئی تھی۔ ظہیر الدین بابر کا تعلق تیمور لنگ خاندان سے تھا۔ وہ بابر کے لقب سے جانا جاتا تھا، جس کا مطلب ہے شیر۔ سینٹرل ایشیاء میں ایک خطے کی شہنشایت اسی کے خاندان کے پاس تھی۔ اس کے باپ نے موجودہ ” ازبکستان“ پر حکومت کی۔ Andeijan اس کا دارالحکومت تھا۔ اس نے اسی شہر میں 23 فروری 1483ء کو آنکھ کھولی۔ باپ کا پورا نام عمر شریف مرزا رکھا تھا، تاہم وہ امیر فرخانہ کے لقب سے مشہور تھا۔ اس کی ماں قتلک نگار خانم مغل بادشاہ مرزا خان کی بیٹی تھیں۔

(یہ تحریر روزنامہ دنیا کے میگزین میں شائع ہوئی)

Akbar

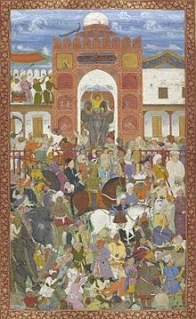

Akbar known as Akbar the Great, was Mughal Emperor from 1556 until his death. He was the third and greatest ruler of the Mughal Dynasty in India. Akbar succeeded his father, Humayun, under a regent, Bairam Khan, who helped the young emperor expand and consolidate Mughal domains in India. A strong personality and a successful general, Akbar gradually enlarged the Mughal Empire to include nearly all of the Indian Subcontinent north of the Godavari river. His power and influence, however, extended over the entire country because of Mughal military, political, cultural, and economic dominance. To unify the vast Mughal state, Akbar established a centralised system of administration throughout his empire and adopted a policy of conciliating conquered rulers through marriage and diplomacy.

Akbar known as Akbar the Great, was Mughal Emperor from 1556 until his death. He was the third and greatest ruler of the Mughal Dynasty in India. Akbar succeeded his father, Humayun, under a regent, Bairam Khan, who helped the young emperor expand and consolidate Mughal domains in India. A strong personality and a successful general, Akbar gradually enlarged the Mughal Empire to include nearly all of the Indian Subcontinent north of the Godavari river. His power and influence, however, extended over the entire country because of Mughal military, political, cultural, and economic dominance. To unify the vast Mughal state, Akbar established a centralised system of administration throughout his empire and adopted a policy of conciliating conquered rulers through marriage and diplomacy. In order to preserve peace and order in a religiously and culturally diverse empire, he adopted policies that won him the support of his non-Muslim subjects. Eschewing tribal bonds and Islamic state identity, Akbar strived to unite far-flung lands of his realm through loyalty, expressed through a Persianised culture, to himself as an emperor who had near-divine status. Mughal India developed a strong and stable economy, leading to commercial expansion and greater patronage of culture. Akbar himself was a great patron of art and culture. He was fond of literature, and created a library of over 24,000 volumes written in Sanskrit, Hindustani, Persian, Greek, Latin, Arabic and Kashmiri, staffed by many scholars, translators, artists, calligraphers, scribes, bookbinders and readers.

Holy men of many faiths, poets, architects and artisans adorned his court from all over the world for study and discussion. Akbar’s courts at Delhi, Agra, and Fatehpur Sikri became centers of the arts, letters, and learning. Perso-Islamic culture began to merge and blend with indigenous Indian elements, and a distinct Indo-Persian culture emerged characterised by Mughal style arts, painting, and architecture. Disillusioned with orthodox Islam and perhaps hoping to bring about religious unity within his empire, Akbar promulgated Din-i-Ilahi, a syncretic creed derived from Islam, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, and Christianity. A simple, monotheistic cult, tolerant in outlook, it centered on Akbar as a prophet, for which he drew the ire of the ulema and orthodox Muslims.

Isa Khan Niazi

Isa Khan Niazi (Pashto: عیسی خان نيازي) was an Afghan noble in the court of Sher Shah Suri and his son Islam Shah Suri, of the Sur dynasty, who fought the Mughal Empire.

Isa khan Niazi was born in 1453 and his last brother was born in 1478. He died in 1548 at the age of 95 in Delhi. The time of 1451 – 1525 was the golden period for these khans, It was the time when Lodhis were completely dominated in subcontinent (Hindustan). Isa Khan Niazi was a prominent member among the Ruling family. Being in the same tribal unit of nobels like Ibrahim Lodhi, Sher Shah Suri . The large part these families was attached with Delhi Derbar.

In the honor of great war of Haybat Khan Sher Shah Suri awarded Isa Khan Niazi a title Azam – e – Hyumayoo and also made him governor of Multan and send him to Multan in area Pergani Kuchi (present Mianwali) there were great confusion build up between Haybat Khan Niazi (father genealogy of habit is given bhumbra’s genealogy) and Sher Shah Suri and this confusion ended with mutiny.

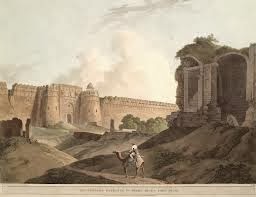

Tomb of Isa Khan

Isa Khan’s tomb was built during his lifetime ca 1547-48 AD, is situated near the Mughal Emperor Humayun‘s Tomb complex in Delhi which was built later, between 1562-1571 AD. Built within an enclosed octagonal garden, it bears a striking resemblance to other tombs of Sur dynasty monuments in the Lodhi Gardens. This octagonal tomb has distinct ornamentation in the form of canopies, glazed tiles and lattice screens and a deep veranda, around it supported by pillars. It stand south of the Bu Halima garden just as visitors enter the complex. An inscription on a red sandstone slab indicated that the tomb is of Masnad Ali Isa Khan, son of Niyaz Aghwan, the Chief chamberlain, and was built during the reign of Islam Shah Suri, son of Sher Shah, in 1547-48 A.D.[1] On 5 August 2011 the restoration work on this tomb in New Delhi led to the discovery of the India’s oldest sunken garden. Isa Khan’s garden tomb in the enclosed area of Humayun’s Tomb World Heritage Site in the Capital of India can now be considered the earliest example of a sunken garden in India – attached to a tomb – a concept later developed at Akbar’s Tomb and at the Taj Mahal.[2]

Mosque of Isa Khan

At the edge of the complex, across from the tomb, lies a mosque with noticeable mehrabs. It is known as Isa Khan’s Mosque, and was built along with the tomb. Many of the architectural details present in these structures can be seen further evolved in the main Humayun’s tomb, though on a much grander scale, such as the tomb being placed in a walled garden enclosure.[3]

Aurangzeb

Abul Muzaffar Muhi-ud-Din Mohammad Aurangzeb, commonly known as Aurangzeb and by his imperial title Alamgir (“world-seizer” or “universe-seizer”) was the sixth Mughal Emperor and ruled over most of the Indian subcontinent. His reign lasted for 49 years from 1658 until his death in 1707. Aurangzeb was a notable expansionist and during his reign, the Mughal Empire reached its greatest extent. He was among the wealthiest of the Mughal rulers with an annual yearly tribute of £38,624,680 (in 1690). He was a pious Muslim, and his policies partly abandoned the legacy of Akbar’s secularism, which remains a very controversial aspect of his reign. During his lifetime, victories in the south expanded the Mughal Empire to more than 3.2 million square kilometres and he ruled over a population estimated as being in the range of 100-150 million subjects. He was a strong and effective ruler, but with his death the great period of the Mughal dynasty came to an end, and central con

Bundela War

On 13 December 1634, Aurangzeb was given his first command, comprising 10,000 horse and 4000 troopers. He was allowed to use the red tent, which was an imperial prerogative. Subsequently, Aurangzeb was nominally in charge of the force sent to Bundelkhand with the intent of subduing the rebellious Bundela leader, Jujhar Singh, who had attacked another territory in defiance of Shah Jahan’s policy and was refusing to atone for his actions.[4] By arrangement, Aurangzeb stayed in the rear, away from the fighting, and took the advice of his generals as the Mughal Army gathered and commenced the Siege of Orchha in 1635.[citation needed] The campaign was successful and Singh was removed from power.[4]

Viceroy

Aurangzeb took up his new post as the Viceroy of the Deccan in 1636.[6] After Shah Jahan’s vassals had been devastated by the alarming expansion of Ahmednagar during the reign of the Nizam Shahi boy-prince Murtaza Shah III, the emperor dispatched Aurangzeb, who in 1636 brought the Nizam Shahi dynasty to an end.[citation needed]. In 1637, Aurangzeb married the Safavid princess, Dilras Banu Begum, also known as Rabia-ud-Daurani. She was his first wife and chief consort.[7][8] He also had an infatuation with a slave girl, Hira Bai — whose death at a young age greatly affected him. In his old age, he was under the charms of his concubine, Udaipuri Bai. The latter had formerly been a companion to Dara Shikoh.[9] In the same year, 1637, Aurangzeb was placed in charge of annexing the small Rajput kingdom of Baglana, which was achieved with ease.[10]

In 1644, Aurangzeb’s sister, Jahanara, was burned when the chemicals in her perfume were ignited by a nearby lamp while in Agra. This event precipitated a family crisis with political consequences. Aurangzeb suffered his father’s displeasure when he returned to Agra three weeks after the event, instead of immediately. Shah Jahan had been nursing Jahanara back to health in that time and thousands of vassals had arrived in Agra to pay their respects.[citation needed] Shah Jahan was outraged to see Aurangzeb enter the interior palace compound in military attire and immediately dismissed him from his position of Viceroy of the Deccan, Aurnagzeb was also no longer allowed to use red tents, with that privilege being handed to Dara Shikoh, or associate himself with the official military standard of the Mughal emperor.[citation needed]

In 1645, he was barred from the court for seven months and mentioned his grief to fellow Mughal commanders. Thereafter, Shah Jahan appointed him governor of Gujarat where he served well and was rewarded for bringing stability.[citation needed] In 1647, Shah Jahan moved him from Gujarat to be governor of Balkh, replacing Aurangzeb’s younger brother, Murad Baksh, who had proved ineffective there. The area was under attack from Uzbek and Turkoman tribes. Whilst the Mughal artillery and muskets were a formidable force, so too were the skirmishing skills of their opponents. The two sides were in stalemate and Aurangzeb discovered that his army could not live off the land, which was devastated by war. With the onset of winter, he and his father had to make a largely unsatisfactory deal with the Uzbeks, giving away territory in exchange for nominal recognition of Mughal sovereignty. The Mughal force suffered still further with attacks by Uzbeks and other tribesmen as it retreated through snow to Kabul. By the end of this two-year campaign, into which Aurangzeb had been plunged at a late stage, a vast sum of money had been expended for little gain.[11]

Further inauspicious military involvements followed, as Aurangzeb was appointed governor of Multan and Sindh. His efforts in 1649 and 1652 to dislodge the Safavids at Kandahar, which they had recently retaken after a decade of Mughal control, both ended in failure as winter approached. The logistical problems of supplying an army at the extremity of the empire, combined with the poor quality of armaments and the intransigence of the opposition have been cited by John Richards as the reasons for failure, and a third attempt in 1653, led by Dara Shikoh, met with the same outcome.[12]Dara Shikoh’s appointment followed the removal of Aurangzeb, who once again took the role of viceroy in the Deccan. He regretted this and harboured feelings that Dara had manipulated the situation to serve his own ends. Aurangbad’s two jagirs (land grants) were moved there as a consequence of his return and, because the Deccan was a relatively impoverished area, this caused him to lose out financially. So poor was the area that grants were required from Malwa and Gujarat in order to maintain the administration and the situation caused ill-feeling between father and son. Shah Jahan insisted that things could be improved if Aurangzeb made efforts to develop cultivation, but the efforts that were made proved too slow in producing results to satisfy the emperor.[13]

Aurangzeb proposed to resolve the situation by attacking the dynastic occupants of Golconda (the Qutb Shahis) and Bijapur (the Adil Shahis). As an adjunct to resolving the financial difficulties, the proposal would also extend Mughal influence by accruing more lands. Again, he was to feel that Dara had exerted influence on his father: believing that he was on the verge of victory in both instances, Aurangzeb was frustrated that Shah Jahan chose then to settle for negotiations with the opposing forces rather than pushing for complete victory.[13trol of the sub-continent declined rapidly.

Nur-ud-din Mohammad Salim Jahangir

Nur-ud-din Mohammad Salim, known by his imperial name Jahangir (30 August, 1569-28 October, 1627), was the fourth Mughal Emperor who ruled from 1605 until his death in 1627.

Jahangir was the eldest surviving son of Mughal Emperor Akbar and was declared successor to his father from an early age. Impatient for power, however, he revolted in 1599 while Akbar was engaged in the Deccan. Jahangir was defeated, but ultimately succeeded his father as Emperor in 1605 due to the immense support and efforts of his step-mothers, Empress Ruqaiya Sultan Begum and Salima Sultan Begum, both of whom wielded great influence over Akbar and favoured Jahangir as his successor.[1] The first year of Jahangir’s reign saw a rebellion organized by his eldest son Khusrau Mirza. The rebellion was soon put down; Khusrau was brought before his father in chains. After subduing and executing nearly 2000 members of the rebellion, Jahangir blinded his renegade son.

Jahangir built on his father’s foundations of excellent administration, and his reign was characterized by political stability, a strong economy and impressive cultural achievements. The imperial frontiers continued to move forward—in Bengal, Mewar, Ahmadnagar and the Deccan. The only major reversal to the expansion came in 1622 when Shahanshah Abbas, the Safavid Emperor of Persia, captured Kandahar while Jahangir was battling his rebellious son, Khusrau in Hindustan. The rebellion of Khurram absorbed Jahangir’s attention, so in the spring of 1623 he negotiated a diplomatic end to the conflict. Much of India was politically pacified; Jahangir’s dealings with the Hindu rulers of Rajputana were particularly successful, and he settled the conflicts inherited from his father. The Hindu rulers all accepted Mughal supremacy and in return were given high ranks in the Mughal aristocracy.

Jahangir was fascinated with art, science and, architecture. From a young age he showed a leaning towards painting and had an atelier of his own. His interest in portraiture led to much development in this artform. The art of Mughal painting reached great heights under Jahangir’s reign. His interest in painting also served his scientific interests in nature. The painter Ustad Mansur became one of the best artists to document the animals and plants which Jahangir either encountered on his military exhibitions or received as donations from emissaries of other countries. Jahangir maintained a huge aviary and a large zoo, kept a record of every specimen and organised experiments. Jahangir patronized the European and Persian arts. He promoted Persian culture throughout his empire. This was especially so during the period when he came under the influence of his Persian Empress, Nur Jahan, and her relatives, who from 1611 had dominated Mughal politics. Amongst the most highly regarded Mughal architecture dating from Jahangir’s reign is the famous Shalimar Gardens in Kashmir. The world’s first seamless celestial globe was built by Mughal scientists under the patronage of Jahangir.

Jahangir, like his father, was not a strict Sunni Muslim; he allowed, for example, the continuation of his father’s tradition of public debate between different religions. The Jesuits were allowed to dispute publicly with Muslim ulema (theologians) and to make converts. Jahangir specifically warned his nobles that they “should not force Islam on anyone.” Jizya was not imposed by Jahangir. Edward Terry, an English chaplain in India at the time, saw a ruler under which “all Religions are tolerated and their Priests [held] in good esteem.” Jahangir enjoyed debating theological subtleties with Brahmins, especially about the possible existence of avatars. Both Sunnis and Shias were welcome at court, and members of both sects gained high office. Sir Thomas Roe, England‘s first ambassador to the Mughal court, went as far as labelling Jahangir, who was sympathetic to Christianity, an atheist.

Jahangir was not without his vices.

He set the precedent for sons rebelling against their emperor fathers and was much criticised for his addiction to alcohol, opium, and women. He was thought of allowing his wife, Nur Jahan, too much power and her continuous plotting at court is considered to have destabilized the imperium in the final years of his rule. The situation developed into open crisis when Jahangir’s son, Khurram, fearing to be excluded from the throne, rebelled in 1622. Jahangir’s forces chased Khurram and his troops from Fatehpur Sikri to the Deccan, to Bengal and back to the Deccan, until Khurram surrendered unconditionally in 1626. The rebellion and court intrigues that followed took a heavy toll on Jahangir’s health. He died in 1627 and was succeeded by Khurram, who took the imperial throne of Hindustan as the Emperor Shah Jahan. Jahangir is considered one of the greatest Mughal Emperors by scholars and the fourth of the Grand Mughals in Indian historiography. Much romance has gathered around his name, and the tale of his illicit relationship with the Mughal courtesan, Anarkali, has been widely adapted into the literature, art and cinema of India.

Nasir ud-din Muhammad Humayun

Nasir ud-din Muhammad Humayun was the second Mughal Emperor who ruled a large territory consisting of what is now Afghanistan, Pakistan, and parts of northern India from 1530–1540 and again from 1555–1556. Like his father, Babur, he lost his kingdom early, but with Persian aid, he eventually regained an even larger one. On the eve of his death in 1556, the Mughal empire spanned almost one million square kilometers. He succeeded his father in India in 1530, while his half-brother Kamran Mirza, who was to become a rather bitter rival, obtained the sovereignty of Kabul and Lahore, the more northern parts of their father’s empire. He originally ascended the throne at the age of 23 and was somewhat inexperienced when he came to power.

Humayun lost Mughal territories to the Pashtun noble, Sher Shah Suri, and, with Persian aid, regained them 15 years later. Humayun’s return from Persia, accompanied by a large retinue of Persian noblemen, signaled an important change in Mughal court culture. The Central Asian origins of the dynasty were largely overshadowed by the influences of Persian art, architecture, language and literature. There are many stone carvings and thousands of Persian manuscripts in India from the time of Humayun. Subsequently, in a very short time, Humayun was able to expand the Empire further, leaving a substantial legacy for his son, Akbar. His peaceful personality, patience and non-provocative methods of speech earned him the title ’Insān-i-Kamil (‘Perfect Man’), among the Mughals

With this Persian Safavid aid Humayun took Kandahar from Askari Mirza after a two-week siege. He noted how the nobles who had served Askari Mirza quickly flocked to serve him, “in very truth the greater part of the inhabitants of the world are like a flock of sheep, wherever one goes the others immediately follow”. Kandahar was, as agreed, given to the Shah of Persia who sent his infant son, Murad, as the Viceroy. However, the baby soon died and Humayun thought himself strong enough to assume power. Humayun now prepared to take Kabul, ruled by his brother Kamran Mirza. In the end, there was no actual siege. Kamran Mirza was detested as a leader and as Humayun’s Persian army approached the city hundreds of Kamran Mirza’s troops changed sides, flocking to join Humayun and swelling his ranks. Kamran Mirza absconded and began building an army outside the city. In November 1545, Hamida and Humayun were reunited with their son Akbar, and held a huge feast. They also held another, larger, feast in the childs’ honour when he was circumcised.

However, while Humayun had a larger army than his brother and had the upper hand, on two occasions his poor military judgement allowed Kamran Mirza to retake Kabul and Kandahar, forcing Humayun to mount further campaigns for their recapture. He may have been aided in this by his reputation for leniency towards the troops who had defended the cities against him, as opposed to Kamran Mirza, whose brief periods of possession were marked by atrocities against the inhabitants who, he supposed, had helped his brother. His youngest brother, Hindal Mirza, formerly the most disloyal of his siblings, died fighting on his behalf. His brother Askari Mirza was shackled in chains at the behest of his nobles and aides. He was allowed go on Hajj, and died en route in the desert outside Damascus.

Humayun’s other brother, Kamran Mirza, had repeatedly sought to have Humayun killed, and when in 1552 he attempted to make a pact with Islam Shah, Sher Shah’s successor, he was apprehended by a Gakhar. The Gakhars were one of only a few groups of people who had remained loyal to their oath to the Mughals. Sultan Adam of the Gakhars handed Kamran Mirza over to Humayun. Humayun was tempted to forgive his brother, however he was warned that allowing Kamran Mirza’s continuous acts to go unpunished could foment rebellion within his own ranks. So, instead of killing his brother, Humayun had Kamran Mirza blinded which would end any claim to the throne. He sent him on Hajj, as he hoped to see his brother absolved of his hateful sins, but he died close to Mecca in the Arabian Peninsula in 1557..[1][full citation needed]

Sher Shah Suri

Sher Shah Suri , also known as Sher Khan, “The Lion King”) was the founder of the Sur Empire in North India, with its capital at Delhi.[3] An ethnic Pashtun, Sher Shah took control of the Mughal Empire in 1540. After his accidental death in 1545, his son Islam Shah became his successor.[4][5][6][7][8] He first served as a private before rising to become a commander in the Mughal army under Babur and then as the governor of Bihar. In 1537, when Babur’s son Humayun was elsewhere on an expedition, Sher Khan overran the state of Bengal and established the Sur dynasty.[9] A brilliant strategist, Sher Shah proved himself a gifted administrator as well as an able general. His reorganization of the empire laid the foundations for the later Mughal emperors, notably Akbar the Great, son of Humayun.[9]

During his five year rule from 1540 to 1545, he set up a new civic and military administration, issued the first Rupee and re-organised the postal system of India.[10] He further developed Humayun’s Dina-panah city and named it Shergarh and revived the historical city of Pataliputra as Patna which had been in decline since the 7th century CE.[11] He is also famously remembered for killing a fully grown tiger with his bare hands in a jungle of Bihar.[4][9] He extended the Grand Trunk Road from Chittagong in Bangladesh to Kabul in Afghanistan.

Early life and origin

Sher Shah was born as Farid Khan in the present day district of Mahendragarh in south Haryana, earlier part of Hisar district of combined Punjab in India. His grand father Ibrahim Khan Sur was a land lord (Jagirdar) in Narnaul area and represented Delhi rulers of that period. Mazar of Ibrahim Khan Sur still stands as a monument in Narnaul. Tarikh-i Khan Jahan Lodi (MS. p. 151).[2] also confirm this fact. However, the online Encyclopædia Britannica states that he was born in Sasaram (Bihar), in the Rohtas district.[4] He was one of about eight sons of Mian Hassan Khan Sur, a prominent figure in the government of Bahlul Khan Lodi. Sher Khan belonged to the Pashtun Sur tribe (the Pashtuns are known as Afghans in historical Persian language sources).[12] His grandfather, Ibrahim Khan Sur, was a noble paad who was recruited much earlier by Sultan Bahlul Lodi of Delhi during his long contest with the Jaunpur Sultanate.

“It was at the time of this bounty of Sultán Bahlol, that the grandfather of Sher Sháh, by name Ibráhím Khán Súri,*[The Súr represent themselves as descendants of Muhammad Súri, one of the princes of the house of the Ghorian, who left his native country, and married a daughter of one of the Afghán chiefs of Roh.] with his son Hasan Khán, the father of Sher Sháh, came to Hindu-stán from Afghánistán, from a place which is called in the Afghán tongue “Shargarí,”* but in the Multán tongue “Rohrí.” It is a ridge, a spur of the Sulaimán Mountains, about six or seven kos in length, situated on the banks of the Gumal. They entered into the service of Muhabbat Khán Súr, Dáúd Sáhú-khail, to whom Sultán Bahlol had given in jágír the parganas of Hariána and Bahkála, etc., in the Panjáb, and they settled in the pargana of Bajwára.”[2]—Abbas Khan Sarwani, 1580

During his early age, Farid was given a village in Fargana, Delhi(comprising present day districts of Bhojpur, Buxar, Bhabhua of Bihar) by Omar Khan, the counselor and courtier of Bahlul Khan Lodi. Farid Khan and his father, who had several wives, did not get along for a while so he decided to run away from home. When his father discovered that he fled to serve Jamal Khan, the governor of Jaunpur, Uttar Pradesh, he wrote Jamal Khan a letter that stated:

“Faríd Khán, being annoyed with me, has gone to you without sufficient cause. I trust in your kindness to appease him, and send him back; but if refusing to listen to you, he will not return, I trust you will keep him with you, for I wish him to be instructed in religious and polite learning.”[13]

Jamal Khan had advised Farid to return home but he refused. Farid replied in a letter:

“If my father wants me back to instruct me in learning, there are in this city many learned men: I will study here.”[13]

Conquering Bihar and Bengal

Farid Khan started his service under Bahar Khan Lohani, the Mughal Governor of Bihar.[1][4] Because of his valor, Bahar Khan rewarded him the title Sher Khan (Tiger Lord). After the death of Bahar Khan, Sher Khan became the regent ruler of the minor Sultan, Jalal Khan. Later sensing the growth Sher Shah’s power in Bihar, Jalal sought assistance of Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah, the independent Sultan of Bengal. Ghiyasuddin sent an army under General Ibrahim Khan. But, Sher Khan defeated the force at the battle of Surajgarh in 1534. Thus he achieved complete control of Bihar.[1]In 1538, Sher Khan attacked Bengal and defeated Ghiyashuddin Shah.[1] But he could not capture the kingdom because of sudden expedition of Emperor Humayun.[1] In 1539, Sher Khan faced Humayun in the battle of Chausa. He forced Humayun out of India. Assuming the title Sher Shah, he ascended the throne of Delhi.[4]

Battle of Sammel

In 1543, Sher Shah Suri set out against Rajputana with a huge force of 80,000 cavalry. With an army of 50,000 cavalry, Maldeo Rathore advanced to face Sher Shah’s army. Instead of marching to the enemy’s capital Sher Shah halted in the village of Sammel in the pargana of Jaitaran, ninety kilometers east of Jodhpur. After one month, Sher Shah’s position became critical owing to the difficulties of food supplies for his huge army. To resolve this situation, Sher Shah resorted to a cunning ploy. One evening, he dropped forged letters near the Maldeo’s camp in such a way that they were sure to be intercepted. These letters indicated, falsely, that some of Maldeo’s army commanders were promising assistance to Sher Shah. This caused great consternation to Maldeo, who immediately (and wrongly) suspected his commanders of disloyalty. Maldeo left for Jodhpur with his own men, abandoning his commanders to their fate.

After that Maldeo’s innocent generals Jaita and Kunpa fought with the just 20,000 men against an enemy force of 80,000 men. In the ensuing battle of Sammel (also known as battle of Giri Sumel), Sher Shah emerged victorious, but several of his generals lost their lives and his army suffered heavy losses. Sher Shah is said to have commented that “for a few grains of bajra (millet, which is the main crop of barren Marwar) I almost lost the entire kingdom of Hindustan.”After this victory, Sher Shah’s general Khavass Khan took possession of Jodhpur and occupied the territory of Marwar from Ajmer to Mount Abu in 1544. But by July, Maldeo reoccupied his lost territories.

Timur Lang

Timur, Tarmashirin Khan, Emir Timur (Persian: تیمور Timūr, Chagatai: Temür “iron”; 9 April 1336 – 18 February 1405), historically known as Tamerlane[1] (Persian: تيمور لنگ Timūr(-e) Lang, “Timur the Lame”), was a Turko-Mongol ruler of Barlas lineage.[2][3][4] He conquered West, South and Central Asia and founded the Timurid dynasty. He was the grandfather of Ulugh Beg, who ruled Central Asia from 1411 to 1449,[5][6][7] and the great-great-great-grandfather of Babur Beg, founder of the Mughal Empire, which ruled parts of South Asia for around four centuries, from 1526 until 1857.[8][9][10][11][12]

Timur envisioned the restoration of the Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan.[13] As a means of legitimating his conquests, Timur relied on Islamic symbols and language, referring to himself as the Sword of Islam and patronizing educational and religious institutions. He converted nearly all the Borjigin leaders to Islam during his lifetime.[14] His armies were inclusively multi-ethnic. During his lifetime Timur emerged as the most powerful ruler in the Muslim world after defeating the Mamluks of Egypt and Syria, the emerging Ottoman Empire and the declining Sultanate of Delhi. Timur also decisively defeated the Christian Knights Hospitaller at Smyrna, styling himself a Ghazi.[15] By the end of his reign Timur had also gained complete control over all the remnants of the Chagatai Khanate, Ilkhanate, Golden Horde and even attempted to restore the Yuan dynasty.[citation needed]

Timur’s armies were feared throughout Asia, Africa, and Europe,[16] sizable parts of which were laid waste by his campaigns.[17] Scholars estimate that his military campaigns caused the deaths of 17 million people, amounting to about 5% of the world population,[18][19] leading to a predominantly barbaric legacy. Timur is also recognized as a great patron of art and architecture, as he interacted with Muslim intellectuals such as Ibn Khaldun and Hafiz-i Abru Timur was born in Transoxiana, near the City of Kesh (an area now better known as Shahrisabz, “the green city”), some fifty miles south of Samarkand in modern day Uzbekistan, part of the Chagatai Khanate. [21] His father, Taraqai, was a minor noble belonging to the Barlas tribe.[22] The Barlas, who were originally a Mongol tribe[23][24] that became Turkified.[25][26][27] According to Gérard Chaliand, Timur was a Muslim[28] but he saw himself as Genghis Khan’s heir.[28] Though not a Chinggisid,[29] he clearly sought to invoke the legacy of Genghis Khan’s conquests during his lifetime.[30]

At the age of eight or nine, Timur and his mother and brothers were carried as prisoners to Samarkand by an invading Mongol army.[31]In his childhood, Timur and a small band of followers raided travelers for goods, especially animals such as sheep, horses, and cattle.[32] At around 1363, it is believed that Timur tried to steal a sheep from a shepherd but was shot by two arrows, one in his right leg and another in his right hand, where he lost two fingers. Both injuries caused him to be crippled for life. Some believe that Timur suffered his crippling injuries while serving as a mercenary to the khan of Sistan in Khorasan in what is known today as Dasht-i Margo (Desert of Death) in south-west Afghanistan. Timur’s injuries have given him the name of Timur the Lame or Tamerlane by Europeans.[33]

Timur was a Muslim,[34] but while his chief official religious counsellor and advisor was the Hanafi scholar ‘Abdu ‘l-Jabbar Khwarazmi, his particular persuasion is not known. In Tirmidh, he had come under the influence of his spiritual mentor Sayyid Barakah, a leader from Balkh who is buried alongside Timur in Gur-e Amir.[35][36][37] Timur was known to hold Ali and the Ahlul Bayt in high regard and has been noted by various scholars for his “pro-Alid” stance.[38]Despite this, Timur was noted for attacking Shiites on Sunni grounds and therefore his own religious inclinations remain unclear.[39]

Personality

Timur is regarded as a military genius and a tactician, with an uncanny ability to work within a highly fluid political structure to win and maintain a loyal following of nomads during his rule in Central Asia. He was also considered extraordinarily intelligent- not only intuitively but also intellectually.[40] In Samarkand and his many travels, Timur, under the guidance of distinguished scholars was able to learn Persian, Mongolian, and Turkic languages.[41] More importantly, Timur was characterized as an opportunist. Taking advantage of his Turco-Mongolian heritage, Timur frequently used either the Islamic religion or the law and traditions of the Mongol Empire to achieve his military goals or domestic political aims.[42][43]

Military leader

In about 1360 Timur gained prominence as a military leader whose troops were mostly Turkic tribesmen of the region.[28][44] He took part in campaigns in Transoxiana with the Khan of Chagatai. His career for the next ten or eleven years may be thus briefly summarized from the Memoirs. Allying himself both in cause and by family connection with Kurgan, the dethroner and destroyer of Volga Bulgaria, he was to invade Khorasan at the head of a thousand horsemen. This was the second military expedition that he led, and its success led to further operations, among them the subjugation of Khorezm and Urganj.

Following Kurgan’s murder, disputes arose among the many claimants to sovereign power; this infighting was halted by the invasion of the energetic Chagtaid Tughlugh Timur of Kashgar, another descendant of Genghis Khan. Timur was dispatched on a mission to the invader’s camp, which resulted in his own appointment to the head of his own tribe, the Barlas, in place of its former leader, Hajji Beg. The exigencies of Timur’s quasi-sovereign position compelled him to have recourse to his formidable patron, whose reappearance on the banks of the Syr Darya created a consternation not easily allayed. One of Tughlugh’s sons was entrusted with the Barlas’s territory, along with the rest of Mawarannahr (Transoxiana), but he was defeated in battle by the bold warrior he had replaced, at the head of a numerically far inferior force.

Rise to power

It was in this period that Timur reduced the Chagatai khans to the position of figureheads while he ruled in their name. During this period, Timur and his brother-in-law Husayn, who were at first fellow fugitives and wanderers in joint adventures, became rivals and antagonists. The relationship between them began to become strained after Husayn abandoned efforts to carry out Timur’s orders to finish off Ilya Khoja (former governor of Mawarannah) close to Tishnet.[45]

Timur began to gain a following of people in Balkh that consisted of merchants, fellow tribesmen, Muslim clergy, aristocracy and agricultural workers because of his kindness in sharing his belongings with them, as contrasted with Husayn, who alienated these people, took many possessions from them via his heavy tax laws and selfishly spent the tax money building elaborate structures.[46] At around 1370 Husayn surrendered to Timur and was later assassinated by a chief of a tribe, which allowed Timur to be formally proclaimed sovereign at Balkh. He married Husayn’s wife Saray Mulk Khanum, a descendant of Genghis Khan, allowing him to become imperial ruler of the Chaghatay tribe.[47]

One day Aksak Temür spoke thusly:

“Khan Züdei (in China) rules over the city. We now number fifty to sixty men, so let us elect a leader.” So they drove a stake into the ground and said: “We shall run thither and he among us who is the first to reach the stake, may he become our leader”. So they ran and Aksak Timur, as he was lame, lagged behind, but before the others reached the stake he threw his cap onto it. Those who arrived first said: “We are the leaders.” [“But,”] Aksak Timur said: “My head came in first, I am the leader.” Meanwhile, an old man arrived and said: “The leadership should belong to Aksak Timur; your feet have arrived but, before then, his head reached the goal.” So they made Aksak Timur their prince.[48][49]

Legitimization of Timur’s rule

Timur’s Turco-Mongolian heritage provided opportunities and challenges as he sought to rule the Mongol Empire and the Muslim world. According to the Mongol traditions, Timur could not claim the title of khan or rule the Mongol Empire because he was not a descendant of Genghis Khan. Therefore, Timur set up a puppet Chaghatay khan, Suyurghatmish, as the nominal ruler of Balkh as he pretended to act as a “protector of the member of a Chinggisid line, that of Chinggis Khan’s eldest son, Jochi.”[50]

As a result, Timur never used the title of khan because the name khan could only be used by those who come from the same lineage as Genghis Khan himself. Timur instead used the title of amir meaning general, and acting in the name of the Chagatai ruler of Transoxania.[51]To reinforce his position in the Mongol Empire, Timur managed to acquire the royal title of son-in-law when he married a princess of Chinggisid descent.[52]Likewise, Tamerlane could not claim the supreme title of the Islamic world, caliph, because the “office was limited to the Quraysh, the tribe of the Prophet Muhammad.”[53] Therefore, Tamerlane reacted to the challenge by creating a myth and image of himself as a “supernatural personal power””[53] ordained by God. Since Tamerlane had a successful career as a conqueror, it was easy to justify his rule as ordained and favored by God since no ordinary man could be a possessor of such good fortune that resistance would be seen as opposing the will of Allah. Moreover, the Islamic notion that military and political success was the result of Allah’s favor had long been successfully exploited by earlier rulers. Therefore, Tamerlane’s assertions would not have seemed unbelievable to his fellow Islamic people.